The securities laws are designed to protect investors against false or misleading statements. Investors who suffer a loss as a result of purchasing or selling securities based upon such statements typically have recourse under federal and state laws, but those who hold onto shares – “holders” – based upon false or misleading statements, have a much harder time making out viable claims.

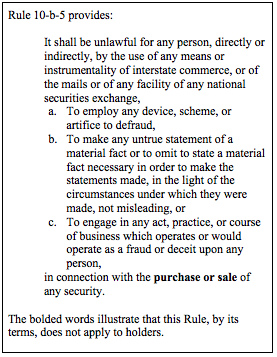

This is in part due to the fact that federal and state securities laws generally contain “in connection with” language – i.e., these laws define a securities violation as the commission of a fraudulent act “in connection with the purchase or sale” of a security.

Another major impediment is proving damages. Many courts wind up dismissing holder claims because of the difficulty in establishing damages, i.e., the amount the investor lost by not selling, because such damagers are oftentimes viewed as speculative.

A third impediment is that the claims may be deemed “derivative” claims as opposed to direct. This means that the claims are held to belong not to the investors, but to the entity that they invested in. This can be an important point because if the entity itself has been forced into bankruptcy, as is often the case, the derivative claims – which investors can bring on behalf of the entity against the defrauding promoters – can no longer be raised by the investors.

On this latter issue, a recent United States District Court, Northern District of Texas decision concludes that under Delaware law, holder claims are direct. In In Re Parkcentral Global Litigation, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 79385 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 5, 2010), the court applied Delaware’s “Tooley test” to determine the issue.

In Tooley, the Delaware Supreme Court held that whether a claim is direct or derivative turns solely on the following questions: “(1) who suffered the alleged harm (the corporation or the suing stockholders, individually); and (2) who would receive the benefit of any recovery or other remedy (the corporation or the stockholders, individually)?” The Parkcentral court went on to note:

Delaware law allows holder claims to be pursued. In [Albert v. ]Alex Brown Management Services, investors asserting such a claim alleged that fund managers breached their fiduciary duties to disclose material information. The Delaware Chancery Court noted that non-disclosure/ misrepresentation claims are generally direct, not derivative, claims. Applying Tooley, the Alex Brown court found that non-disclosure and misrepresentation did not harm the funds, but instead harmed investors who lost the opportunity to withdraw their investments or sue to redeem their interests. Since the investors, not the funds, would receive any recovery, the court held that the plaintiffs could assert such a claim directly.

Another Delaware case, Big Lots v. Bain Capital, illustrates another requirement to make out a viable holder claim and in doing so, distinguishes Alex Brown. For a non-disclosure claim to be direct, plaintiffs must show that defendants were under a duty to disclose. The court stated:

Big Lots claims that nondisclosure claims are generally direct claims, citing this court's decision in Alex.Brown Mgmt. Servs., [cite omitted]. Although the plaintiff is right to note that nondisclosure claims are direct claims where a defendant has "failed to disclose material information when they had a duty to disclose it," the complaint alleges no wellpleaded facts that establish the defendants had any duty to disclose their intention, if any, to conduct the 2002 transaction when they signed the stock purchase agreement in 2000. In the absence of a specific duty to disclose, the plaintiff has only pleaded a set of derivative fiduciary duty claims.

In Anwar v. Fairfield Greenwich, a 2009 Madoff related decision in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, the court reached the same conclusion and expressed the applicable rule as follows:

The principal wrong asserted by the Plaintiffs here is essentially nondisclosure of or failure to learn facts which should have been disclosed based on duties that were independently owed to Plaintiffs.

The key is that there must be a duty of disclosure owed to the plaintiffs-holders by management. This duty may be derived from provisions in the agreements under which the plaintiff-holder purchased its interest or may be otherwise implied under various legal principals.